Thundering Herd + Jitter

20 Sep 2024At Braintree it is no secret that we are big users of Ruby on Rails(RoR). We are also big users of a component of RoR called ActiveJob. ActiveJob is an API abstraction on top of existing background job frameworks such as Sidekiq, Shoryuken and many more. In this blog post, I’m going to share how I was able to get a small feature merged into ActiveJob that stopped a persistent issue.

Context

We have many merchants using our Disputes API, some in realtime in response to a webhook and others on a daily schedule. That means our traffic is highly irregular and difficult to predict which is why we try and use autoscaling and asynchronous processing where feasible.

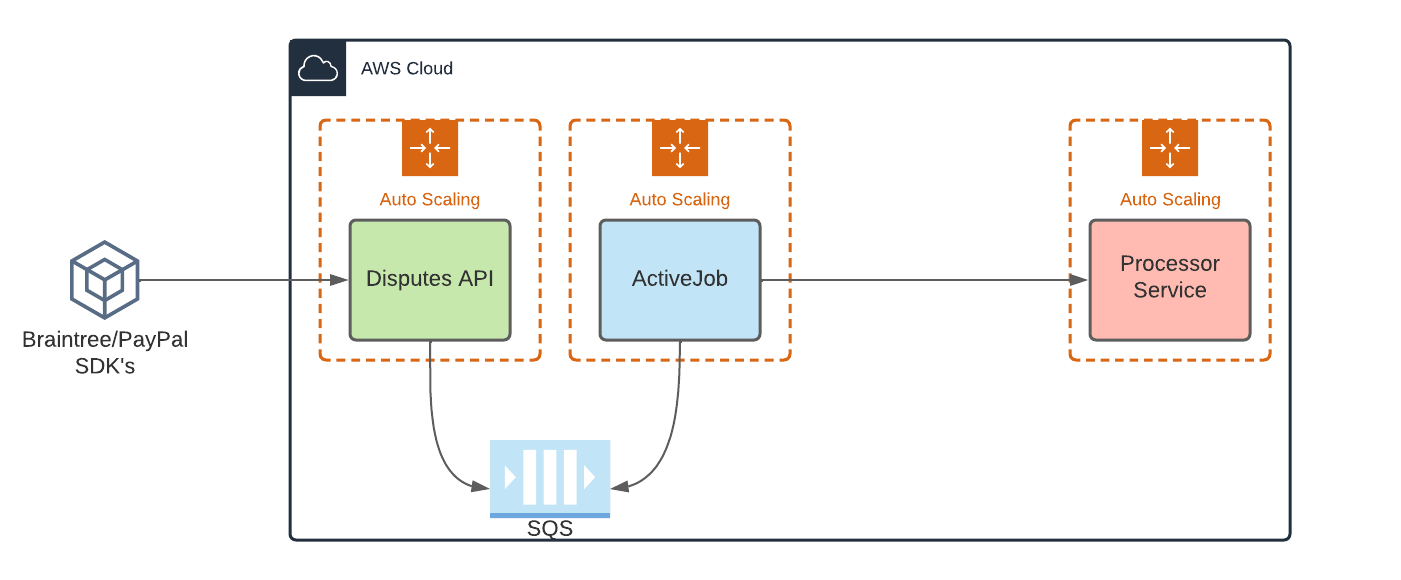

The system architecture:

The architecture is simplified for illustration purposes. The flow though is straightforward, merchants via SDK’s interact with the Disputes API and once finalized, we enqueue a job to SQS for the submission step.

That queue is part of an autoscale policy that scales in and out based on the queue size. The job it performs differs slightly based on the processor we need to deliver the dispute to, but it follows a common flow:

- Generate evidence - we grab everything relevant to a dispute that Braintree has generated and bundle it as metadata

- Compile evidence - Merchants are allowed to submit evidence in many formats, we have to standardize it and prepend metadata from Step 1

- Submit to Processor Service over HTTP

The processor service is abstracted away because as a Gateway-based service we have many payment processors we interact with. The processor service takes realtime traffic over HTTP and then submits to the processor in batches. Every few hours, a cron task wakes up, searches for recent submission requests, batches them into a big zip file and submits them via SFTP to one of our processors. It handles errors and successes and has an API for those various states.

The processor service is HTTP based, also with a simplified autoscale policy.

The Problem

In the job described above, sometimes we would see a number of them had failed over night. ActiveJob errors whenever an unhandled exception occurs and we have a policy in place that DLQ’s the message in those instances (with SQS we simply don’t acknowledge it). We then have a monitor in datadog that tracks the DLQ size and pings us when that figure is > 0.

Dropping a job is not an option, money is on the line for our merchants and we take that very seriously. That means we need systems that are reliable and that also means we need jobs that can handle transient failures with grace. We set up autoscaling because of traffic spikes and robust retry logic based on years of reliability improvements. Still though, we would come into the office some mornings and the DLQ would be in the hundreds with errors like Faraday::TimeoutError, Faraday::ConnectionFailed, and various other Net::HTTP errors.

class EvidenceSubmissionJob < ApplicationJob

retry_on(Faraday::TimeoutError, wait: :exponentially_longer)

retry_on(Faraday::ConnectionFailed, wait: :exponentially_longer)

def perform(dispute)

...

end

end

Why can’t our jobs reach the processor service at certain points in the day? In fact, we had retries for these exact errors so why didn’t the retries work? Once we double checked that jobs were in fact retrying, we realized something else was going on.

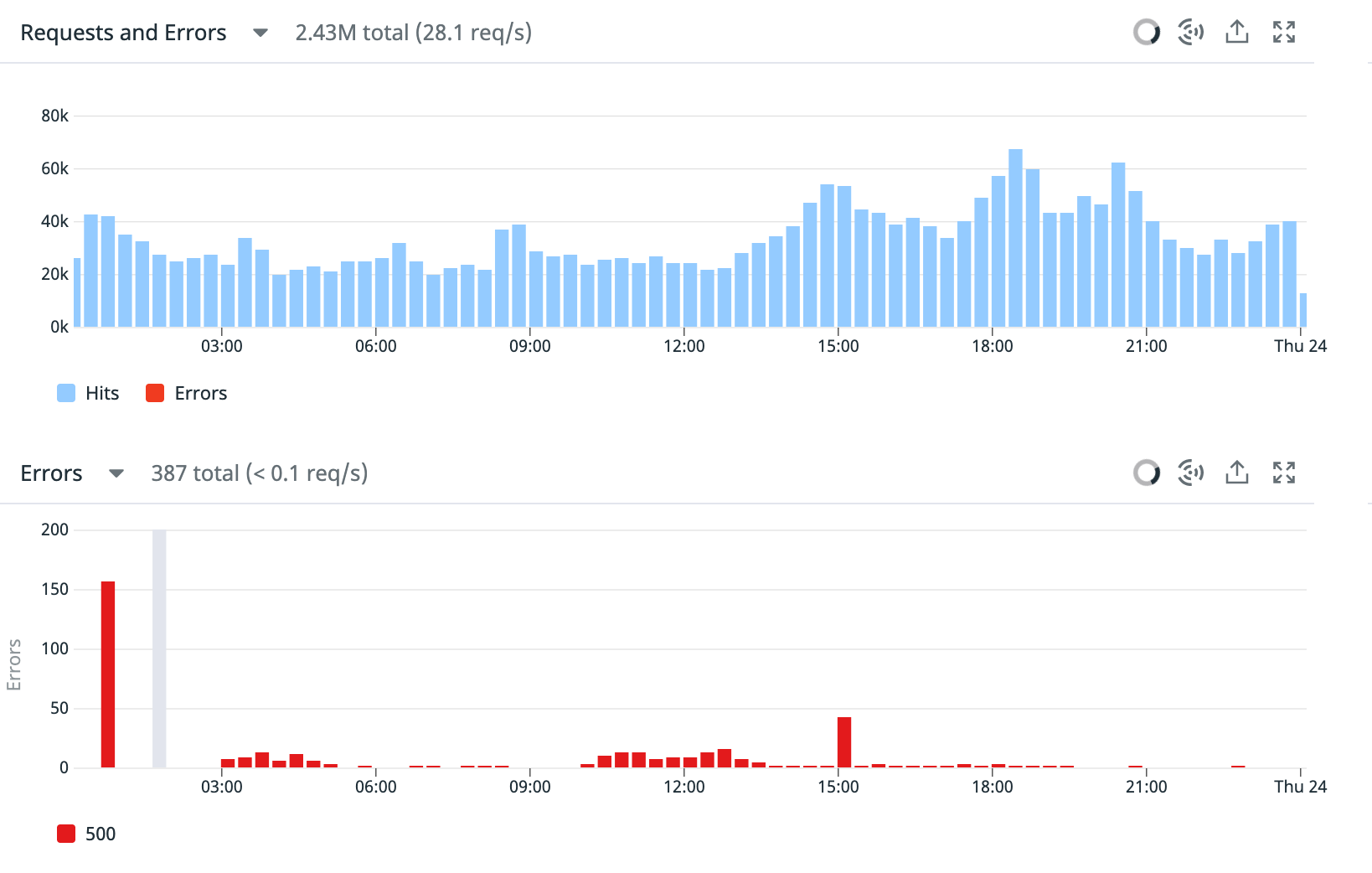

When we looked at our traffic patterns, we could see a big spike of traffic right before the first errors roll in. We figured it’s a scaling issue and that perhaps our scale out policy was too slow but that didn’t explain why the retries didn’t work. If we scaled out and retried, this should eventually succeed.

It wasn’t until we pieced together the timeline that we realized the culprit.

Enter the Thundering herd problem. In the thundering herd problem, a great many processes (jobs in our case) get queued in parallel, they hit a common service and trample it down. Then, our same jobs would retry on a static interval and trample it again. The cycle kept repeating until we exhausted our retries and eventually DLQ’d.

While we had autoscale policies in place for this, our timing was terrible. We would hammer the processor service which would eventually crash it. Then our jobs would go back into the queue to retry N times. The processor service would scale out but some of our retry intervals were so long, the processor service would inevitably scale back in before the jobs retried :facepalm:. Scale in and out policies are a tradeoff of time and money, the faster it can scale in/out the more cost effective but the tradeoff is that we can be underprovisioned for a period of time. This was unfortunate and we could feel the architectural coupling of this entire flow.

We put in place the following plans:

- Stop the bleeding

- Break the coupling

While we were using exponential backoff, it doesn’t exactly stop the Thundering Herd Problem. What we need is to introduce randomness into the retry interval so the future jobs are staggered. ActiveJob did not have randomness or a jitter argument at the time and so I suggested it via a small PR to Rails. We implemented the change locally and immediately saw our DLQ monitors stopped turning red.

Jitter is explained really well by Marc Brooker from AWS, the gist is that if you have 100 people run to a doorway, the doorway might come crashing down. If instead everyone ran at different speeds and arrived with somewhat random intervals, the doorway is still usable and the queue pressure is significantly lessened. At least, that’s how I explained it to my kids (except I told them they’re still not allowed to run in the house).

The code for the animations can be found here.